Coffee

Coffee is a very good example of the way in which global trade can make it difficult for farmers and workers in developing countries to earn a decent living, and how Fairtrade can help them. For both reasons we have made it our business to learn a lot about it, and in this we have been helped directly by the coffee farmers in Choche, Ethiopia, with whom for some years we had a friendship link.

(*Please note this article was published in 2016 – so please check all figures for up to date accuracy if required.)

Origins

Coffee originated in Ethiopia. According to legend it was discovered over 1000 years ago by a young goatherd, named Kaldi, who noticed his herd getting very frisky after eating the red cherries off a wild bush in the forest. The place where that is supposed to have happened is, in fact, Choche!

The photo shows ripe arabica coffee cherries (see next) ready for harvesting, which happens in Choche between late September and early December. Each cherry contains two little green beans which are extracted in one of two ways: by sun drying and then removing the dried flesh in a hullery; or wet processing in a pulpery, washing them in tanks and then drying the beans on racks in the sun.

Types of Coffee

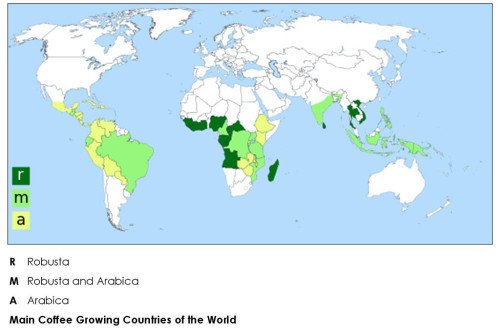

There are two types of commercial coffee: arabica and robusta. Arabica, grown at high tropical altitudes and producing the finest coffee, accounts for 60% to 70% of world production. All Ethiopia’s coffee is arabica. Robusta, grown at lower altitudes, is much more bitter and acid, and accounts for the rest. Arabica is used in ground coffees and robusta in instant coffees (though blended with some arabica to make it drinkable). The global price of arabica is set on the New York Board of Trade (NYBOT) Coffee Exchange and the price of robusta on the London International Financial Futures and Options Exchange (LIFFE). In both markets a great deal of speculation takes place.

The map show the distribution of the two types within the tropics and sub-tropics.

Size of the Market

After oil, coffee is the second most traded commodity in the world. Today coffee exports are worth $20 billion and the value of the global retail market worth over $170 billion (2012 figure). In 2014, 52 of the 70 countries coffee growing were involved in its export.

Most coffee is processed in consuming countries, which, therefore, benefit from the immense added value which comes from the roasting of ground coffees and the manufacturing instant coffees. However, the initial quality checking is done in the producing countries through coffee ‘cupping’, as shown in the photograph.

Producers & Consumers

Brazil is the world’s largest producer of arabica and Vietnam the largest producer of robusta. Over 60% of all coffee is produced in just four countries: Brazil, Vietnam, Colombia and Indonesia. After these four Ethiopia is the next largest producer, accounting for just over 4% of the world market. USA is the biggest importer, followed by Germany and Italy. The Finns are the greatest consumers per capita. About 30% of all coffee is drunk in producing countries; the rest is exported.

Ethiopia is unique in that coffee drinking has been part of their culture for centuries. In fact about 50% of their home-grown coffee is consumed in-country by people of all income groups – rich and poor. Image shows Negash drinking at a roadside café.

The Farmers & Their Farms

Most coffee is grown on very small farms, the rest on plantations. In Choche the average coffee farm size is about 1 hectare and in southern Ethiopia farms are much smaller than that. Worldwide, coffee provides a living for 25 million farmers and their families (in total that’s between 120 and 150 million people). In Ethiopia 15 million people are either directly or indirectly dependent of coffee. Coffee growing is highly labour intensive. Because of the way the market works, most coffee farmers are poor, and in some years do not even cover their costs.

Image shows Iskire Aba Oli coffee picking on her family farm in Choche in late October at the height of the harvesting season.

Coffee's Importance to Countries

For countries that produce it, coffee exports generate a significant proportion of national income and are a vital source of the foreign exchange earnings which governments rely on to improve health, education, infrastructure and other social services. For instance, Burundi relies on coffee for 60 per cent of its export earnings, Ethiopia a third, Honduras for a quarter, Nicaragua for nearly a fifth. So if world coffee prices are low then the economies of these countries are badly hit.

Image shows the Ethiopian government processing facility in Addis Ababa, where lines of women inspect every coffee bean destined for export. It is tedious work, not well paid, but in a country of high unemployment it is a job.

Coffee Supply Chains

These are often complex, with beans sometimes changing hands dozens of times on the journey from grower to consumer. These chains have long been dominated by a small number of very large and very profitable multinational trading and roasting companies. Just four companies – ECOM, Louis Dreyfus, Neumann and VOLCAFE – control around 40 per cent of global coffee trade.

Image again shows the Ethiopian government’s central processing facility, into which most of the country’s coffee is brought and out of which it is sent for export. Every sack is carried on the shoulders of very tough men in poorly paid work, but with high unemployment it provides some security.

The Farmers' Share of the Market

While within the food and drink industry coffee is the most profitable of all beverages, it is a very different story for coffee farmers. The share of the retail value of coffee retained by the producer has fallen over the decades – in the 1970s, producers retained an average of 20 per cent of the retail price of coffee sold in a shop. When oversupply caused prices to crash to historic lows during the coffee crisis of 1994 – 2004, research found coffee growers received just 1-3 per cent of the price of a cup of coffee sold in a café in Europe or North America and 2-6 per cent of the value of coffee sold in a supermarket.

Image shows a clerk buying coffee on behalf of Choche Coffee Farmers’ Cooperative at the end of a day’s harvesting.

To view or print this page as a whole document with additional information on price volatility, the International Coffee Agreement, climate change and Fairtrade …

Please click here to download a pdf.